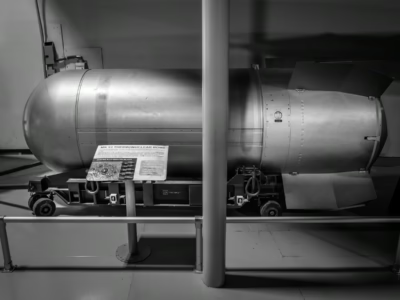

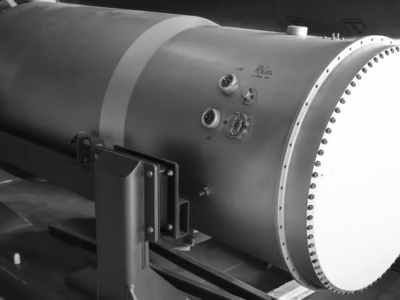

Mark 53 Bomb

Bunker Buster For Moscow’s Buried Command and Control centers

Explosive Power

9 Megaton + a less powerful version

Hiroshima Equivalent Factor

Up to 600x

Dimensions

12 ft., 4 inches x 50 inches

Weight

8850 lbs.

Year(s)

1962–1997

Purpose

A “bunker buster” bomb

About THE MARK 53 Bomb

The sprawl radiating out from Tripoli engulfs the town of Ain Zara. A century ago, it was an oasis, an agricultural center, and on November 1st, 1911, it was the scene of an aerial bombing, grapefruit-sized grenades thrown by hand out of a plane by its pilot, Giulio Gavotti. Though the grenades had arrived at Gavotti’s aerial reconnaissance unit with the understanding that they would be used to bomb the Turks, the enemy in the Italo-Turkish War, no orders had been given. So Gavotti, an enterprising young man in those less structured times, took it upon himself to be the first in his unit to drop bombs from an airplane.

He dropped four of his grenades, three on Ain Aara and one up by the coast, on the Tajura Oasis. Gavotti, as he navigated his Etrich Taube monoplane—an open-frame, single-winged early aircraft that looked as much like an ornithopter from Frank Herbert’s Dune as a modern airplane, stored three of the grenades in a box by his side as he flew and the fourth in his pocket. He tossed the first grenade over the side—taking care to miss his own wing—and became not just the first pilot in his unit to drop a bomb but the first pilot ever to drop a bomb on an enemy.

The bomber was born and soon the idea—still a far-off dream—of decisive air power took hold. The stagnant slaughter of World War I only magnified the hopes of those who felt that air power was the answer to the slow death grind on the ground, a way to strike the enemy cleanly and quickly. A more sophisticated way of war, a more modern kind of war.

World War II was a laboratory, testing theories of air power. The total war of the combatants enlarged not only the production of war material but also the perception of the enemy, the target list enlarged to include industrial areas, to break the manufacturing capability of the enemy, enlarged to include entire cities in great fire-bombing raids, to break the will of the enemy by demoralizing its population.

It didn’t work as air power proponents hoped. Though the fire-bombing raids in Japan, for example, killed hundreds of thousands and wrought vast destruction on almost all of Japan’s cities, it weakened but did not break their resolve. There would still need to be a ground invasion, and hundreds of thousands of Americans (and hundreds of thousands of Japanese, too) would need to die before the war, already long lost for Japan, would end. But then the nascent Air Force dropped two atomic bombs and the war did end decisively, the bloody slaughter of a ground invasion averted. Decisive air power as the dominant player in war only needed the advent of nuclear weapons to finally assert itself.

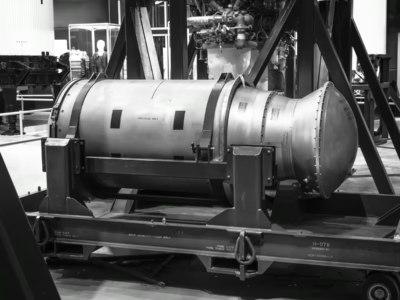

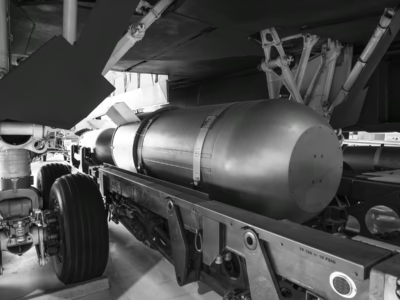

When the Mark 53 bomb was first built in 1961 this bloodline in the military thought’s evolution had reached its pinnacle. The most powerful bombs were city-destroying behemoths, great barrels dropped by parachutes from aircraft flying five or six miles in the sky, the ground an abstraction to the crew, the plane unheard despite its eight enormous engines and barely visible. Despite being labeled as a “bunker buster” designed to collapse deep underground military command and control centers situated around Moscow, the Mark 53, at nine megatons, would have destroyed Moscow itself, even more so as several of these bombs would be required, at least one for every bunker. A ring of mushroom clouds around the enemy capital, each fireball two miles across.

The loss of civilian life wasn’t unfortunate; it was a bonus. Other nuclear weapons would be used to explicitly attack urban centers, hoping to shock the enemy into a quick surrender, its military bases and population centers both decimated, its ability to wage war and its will to wage war simultaneously obliterated. Air power, if allowed to flex its mighty muscles unencumbered by the constraints of lesser men without the time, training, or inclination for strategic thought, would fight wars and win wars in days, not months or years.

The B53 sits in the yellow-painted room, riding atop its old metal cart, dusty and dirty from the passage of fifty years. The photo was made in 2011 and by that time the bomb was obsolete and had been obsolete for decades. It had been retired and brought back from retirement and then mothballed and then considered for revitalization as a defensive weapon against Earth-destroying satellites. It is the last of its kind, not only the last B53 but the last enormously powerful nuclear weapon from the height of the nuclear go-go years of the Cold War. Soon engineer-morticians at the Pantex plant in Texas, just outside Amarillo, would remove its 300 pounds of high explosives, rendering it inert as far as its explosive ability, and it would no longer be a bomb.

A lot has happened since the B53 was born. The horrors of World War II—and the willingness to engage in the worst of its savagery—have faded into forgetfulness as memories are replaced by movies, as experiences are usurped by histories. The idea of destroying cities for the sake of destroying an enemy’s internal political support and decimating its workforce shrank in importance, and the new bombs, the new missiles—accurate at first enough to hit the target, then accurate enough to hit a specific building at the target, then accurate enough to hit a specific part of the roof of the building at the target—with each iteration needing a less and less powerful warhead to get the job done.

Gallery

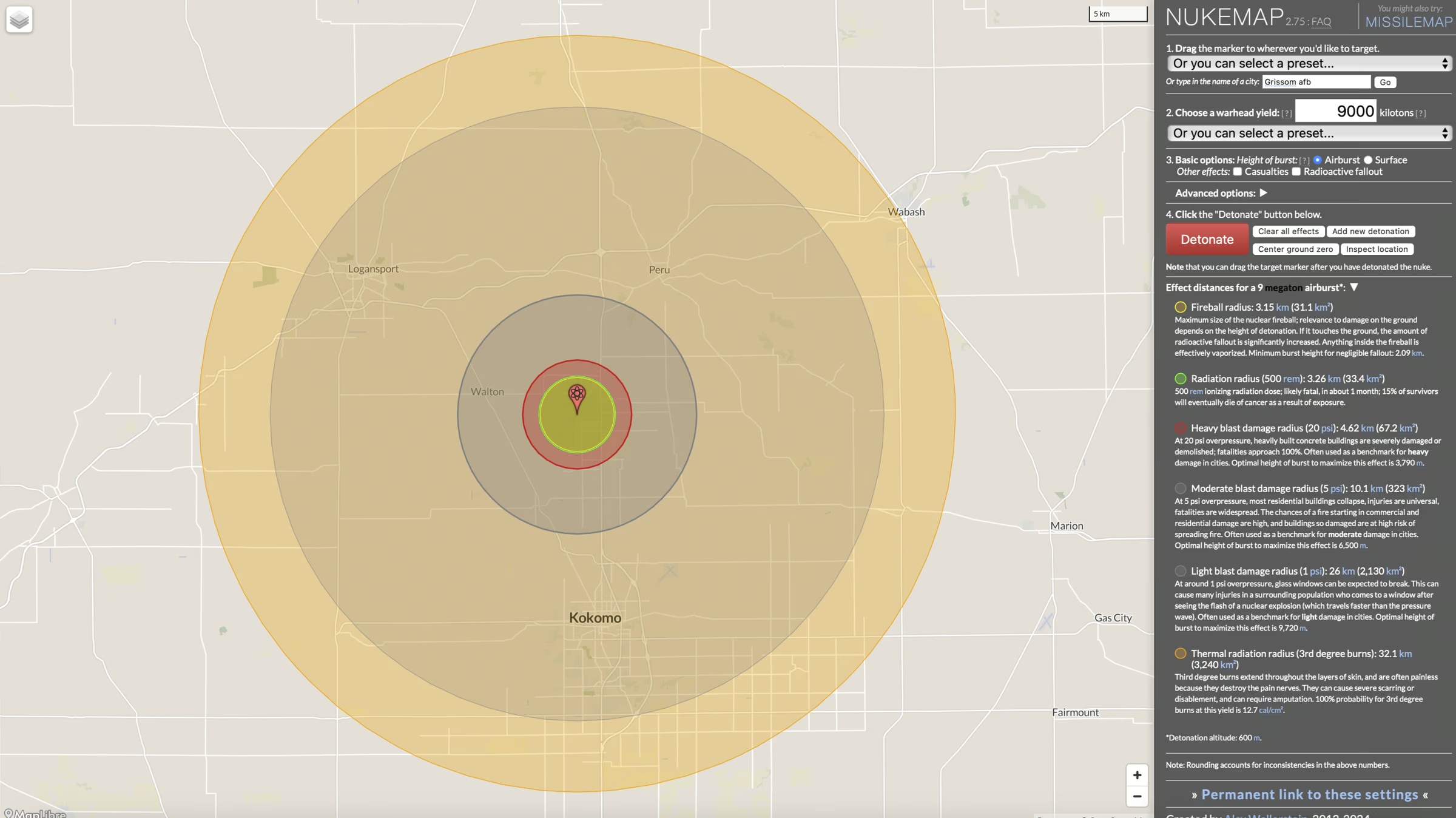

Nukemap

NUKEMAP is a web-based mapping program that attempts to give the user a sense of the destructive power of nuclear weapons. It was created by Alex Wellerstein, a historian specializing in nuclear weapons (see his book on nuclear secrecy and his blog on nuclear weapons). The screenshot below shows the NUKEMAP output for this particular weapon. Click on the map to customize settings.

Videos

Click on the Play button and then the Full screen brackets on the lower right to view each video. Click on the Exit full screen cross at lower right (the “X” on a mobile device) to return.

Further Reading

- Wikipedia, Nuclear Weapons Archive

- Sandia Lab’s “History of the Mark 53 Weapon.”

- A report made by Sandia National Labs describing the characteristics of the B53, its history and, critically, the safey hazards that led to its decommisioning.

- There have been several notable accidents involving the B53. In 1964 a B-52 bomber crashed with two B53s aboard, and that same year a B-58 Hustler caught fire on the runway while carry five nuclear bombs (one was a Mark 53) and burned out-of-control, and in an accident that brought about the removal of the Titan II (and probably the B53) from the US arsenal, a fire and explosion (non-nuclear) in a Titan II missile silo near Damascus, Arkansas in 1980. The book Command and Control (on the American Nukes list of best books) tells the story of this accident.

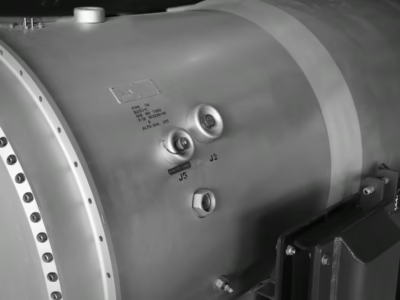

- The Mark 53 was used in modified form for the warhead of the Titan II ICBM (link to American Nukes forthcoming). Note: A picture from a history of the Mark 53 showing the orientation of the physics package within the Titan II warhead.