Mark 39 Bomb

The Bomb We Bombed Ourselves With

Explosive Power

3.8 Megatons

Hiroshima Equivalent Factor

253x

Dimensions

11 feet, 8 inches x 35 inches

Weight

6750 lbs.

Year(s)

1957-1966

Purpose

A smaller and lighter bomb

About THE MARK 39 Bomb

On the same day that John F. Kennedy, only four days into his term, was preparing for his first State of the Union speech to Congress, on the same day that Bob Dylan arrived in New York City and played at Cafe Wha?, his first performance in the city, and on the same day that Billy Reeves, a high school senior, was in his room at his family home in the unincorporated community of Faro, North Carolina, two Mark 39 thermonuclear bombs were falling out of the sky, somewhere above Billy’s house. It was nearly midnight.

It’s worse than it sounds.

The bombs, 6700 pounds and over eleven feet long, were being carried by a B-52G, named Keep 19 on a routine training run out of nearby Seymour Johnson Air Force Base, near Goldsboro, North Carolina. Major Walter Tulloch, commander of the mission, had flown the plane on this flight path before, lifting off from the airfield, flying up the East Coast, out to the Azores, and then back to Greensboro, refueling tankers visiting the thirsty B-52 multiple times during the flight. The plane was one of many B-52s aloft at the same time, part of Operation Chrome Dome which kept bombers in the air, ready to go with live nuclear bombs, in order to gain valuable time in the event of a nuclear war and to prevent the bombers from being caught at their base in the case of a surprise attack.

Keep 19 is heading home when, during the final mid-air refueling, the tanker pilot notifies Major Tulloch that he sees a leak from one of the wings. The leak grows worse and the plane grows difficult to control. It is leaking fast, and as the plane flies the rate of the leak increases. The uneven fuel distribution causes a severe imbalance, putting great stress on the airframe.

There is no public record that the crew gave much thought or took any action regarding the two Mark 39s on board. Both of the bombs were fully assembled weapons with nuclear cores in place within the bombs—but each had a series of safety mechanisms that would prevent a nuclear explosion without explicit action by the crew. There are “safing pins” that must be removed by the crew, there is a timer that ensures that the bombs fall for long enough, there is a barometric pressure device that ensures that the bomb has fallen far enough, and there is an arming switch, set by the pilot before the bomb’s release, that allows the firing signal to travel to the warhead.

There may not have been any need for the crew to give any thought to the bombs or to take any action regarding them. The bombs would just crash with the plane, the high-explosives perhaps detonating but certainly no nuclear explosion.

Thermonuclear bombs work by first detonating an old-fashioned fission bomb, like the one used over Nagasaki. And to detonate that fission bomb, built into the thermonuclear bomb, you need high-explosives. If the high-explosives detonate, and do so correctly (they have to explode in a precise manner) then the whole bomb explodes, the high-explosives setting off the fission bomb, the fission bomb setting off the fusion bomb, all at once. In the case of a Mark 39 that would mean if it detonated on contact with the ground it would create a fireball a mile and a half wide, and a circle of third-degree burns almost twelve miles in diameter. If they both exploded, well, then it’s worse.

On its approach to its home base, the plane begins to fail and the crew attempts to abandon the aircraft. Four of the crew successfully leap from the plane, parachutes on their back, but one, Major Eugene Shelton, is fatally struck by the plane as he jumps.

The plane is breaking up now, the right wing rips away, and the fuselage and its attached left wing begin spinning toward the Earth. It spins and spins and in the centrifuge of the fuselage the bombs break away, into the air, free falling.

The Mark 39 isn’t designed to fall straight to the ground. That would cause a large nuclear explosion much too soon to offer the B-52 any hope of escape. Instead, the bomb is designed to float to Earth by parachute, compromising its targeting precision, perhaps not critical for a 3.8-megaton weapon, in exchange for aircraft survivability.

The first bomb does indeed deploy its parachute, though a later analysis would find that it did not break away from its moorings. Its safing pin is pulled out with no damage to the rod it was attached to, probably due to the centrifugal force upon the lanyards attached to the pins. Its timer turns on, as expected, the barometric pressure device operated, and it lands next to a tree, its nose a foot and a half deep in the soft North Carolina soil, sitting up vertically with its chute tangled in the tree’s branches.

The second bomb’s parachute does not deploy. It free-falls all the way, its timer timing as long as it can, its barometric pressure device monitoring the rapidly increasing air pressure as the bomb races through the thickening atmosphere toward the Earth. The Mark 39 strikes the surface at 700 miles an hour, digging itself almost two dozen feet deep and making a crater nine feet wide. The nuclear core of the thermonuclear part of the bomb shoots deeper, perhaps as deep as 180 feet. Recovery teams will dig as far as they can but the core will not be recovered and the government will ultimately buy an easement on the land, refilling the hole.

The first bomb, tangled in the tree, is found with its arming switch set to “Safe.” The second bomb, when it is dug up, is found with its arming switch set to “Arm.” The second bomb may have armed itself on impact and at the same instant that the wire from the switch to the warhead was severed.

Kennedy gives his speech, an optimistic speech, a few days later. Dylan plays at Cafe Wha? for two weeks after that first show without any need to evacuate. But that night Billy Reeves sees the sky all red and a one-winged B-52 twist violently into the ground and hears his mother cry out that it is the end of the world.

But it is not the end of the world, nor even the end of Billy and his mother.

Gallery

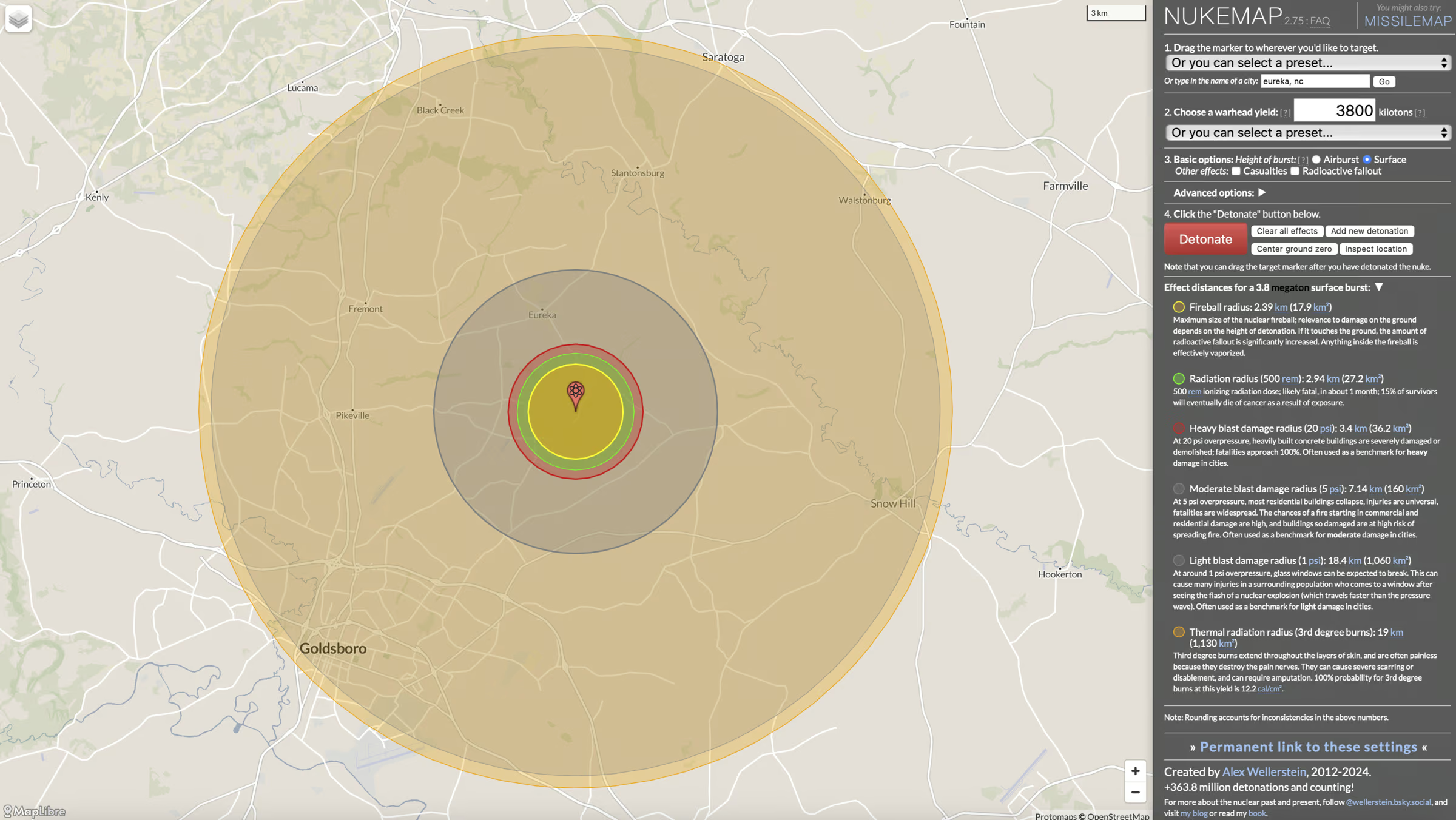

Nukemap

NUKEMAP is a web-based mapping program that attempts to give the user a sense of the destructive power of nuclear weapons. It was created by Alex Wellerstein, a historian specializing in nuclear weapons (see his book on nuclear secrecy and his blog on nuclear weapons). The screenshot below shows the NUKEMAP output for this particular weapon. Click on the map to customize settings.

Videos

Click on the Play button and then the Full screen brackets on the lower right to view each video. Click on the Exit full screen cross at lower right (the “X” on a mobile device) to return.

Further Reading

- Wikipedia

- In 1967 Sandia “published” a classified report on the history of the Mark 39, now available at the Pfeiffer Nuclear Weapons and National Security Archive.

- The Mark 39 is infamous for being involved in several serious nuclear accidents. One of them, when a B-52 broke up on its landing approach and two live Mark 39s were flung from the falling wreckage over North Carolina, is among the most frightening. The basic story is told in this Spectator article as well as in this one in Our State.

- Many of the details of the accident came to light as the result of Eric Schlosser’s efforts and appeared in his book, Command and Control (see pages 245–248). Some of the classified studies that Schlosser referenced were later released to the public (this one, a safety analysis of the Mark 39’s safety mechanisms in the accident, is especially worthwhile) and Schlosser made public an excerpt from an unclassified film, made by Sandia Laboratories, that included a segment on the accident (and here is a link to the full film). Here is Schlosser interviewed about his reporting.

- Parker F. Jones at Sandia National Labs wrote “How I Learned to Love the H-Bomb” in 1969 which analyzes the erroneous claims about the accident.

- Air Force EOD (Explosives Ordinance Division) Airman First Class Earl Smith was the first Air Force personnel on the scene of the Goldsboro accident and was out there for three weeks, digging in the mud. After the accident became public knowledge and especially after senior officer Jack ReVelle, according to Smith, falsely claimed credit for defusing the first bomb, Smith decided to tell his story. This video (linked above, as well) is especially interesting as Smith tells how there was a trap (meant for the Soviets) in the defusing process that would cause the bomb to explode if there wasn’t a specific pause in the disarming process. These links have only a tiny number of views and I have found no reference to his story anywhere else.